The Art of Abstraction

by Josh Crane, on Dec 6, 2019 8:36:46 AM

Many moons ago, I started doing repairing and working on cars and robots for fun. After a few skinned knuckles and dropped wrenches, I learned to appreciate anything that was easy to work on. Frustration was dampened, and I did not have to spend as much time planning how I would work around unnecessary obstacles. When this was not the case, I was frequently annoyed by having to take extra steps, or not understanding why the designers wouldn’t take a little time on the front end to make everyone’s life easier in the future. Only recently have I begun to appreciate these principles in writing code. Some forethought at the outset can go a long way; cutting corners means having to return and fix it later. In the physical world many will refer to a concept called “Design for Service,” but a similar concept in software is abstraction. This concept will allow code to be more flexible and powerful as it is written, and easier to work on in the future.

In code, layers of abstraction refers to certain basic functions that are called as needed by bigger functions. Those larger functions can be used to create the largest functions that will make up the main program. This process repeats until a program is able to carry out its desired function. It seems simple enough; what is the alternative?

The alternative is to have code with no layers at all, that does not call functions but executes one action after another no matter what. While it is possible to add logic in the form of ‘if’ and ‘elseif' conditions, the robot does not have as much freedom to carry out necessary parts of the program at the right times. This code does not allow the robot to make decisions as effectively. Code written this way is also harder to modify should user’s needs change in the future. If a repeated action must be modified, this edit must be done at each instance it is performed in the polyscope program. Lastly, code that is in production without layers of abstraction can be much harder to debug. This yields more down time for the robot.

Layers of abstraction allow the code to be more efficient, and reduce the amount head-scratching at the initial setup as well as trouble shooting. While this concept can apply to code written in the Universal Robots Polyscope interface, which will be touched on here, we will focus on using this principle in URscript, since it gives its user’s much more flexibility.

While creating any code, one of the key tenants is to have one function do one thing. It will carry out one task that may or may not have multiple steps. Those steps will each garner their own function, even if that function is one line of code. Anyone who comes in contact with the program can quickly identify the intended result of any function, as well as the full program. They will also know where to edit the code to obtain the desired result. To illustrate this principle, consider the creation of a childhood favorite: the peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

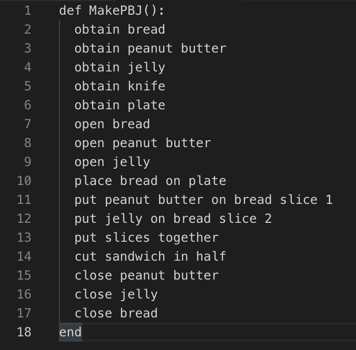

Figure 1: These are basic steps for making a PB&J sandwich

In Figure 1, there is one program that moves through all the steps to create a sandwich. The steps here are redundant, and even though this is a simple and small example, the code can be difficult to read, more-so as complexity is added to your robotic cell. The order in which the sandwich must be made, the amount of peanut butter and jelly applied, and the slices on which they are applied cannot be changed without altering the main program. The program is not very flexible, and can only make the sandwich in a certain way. Let’s add some abstraction and see what it looks like below.

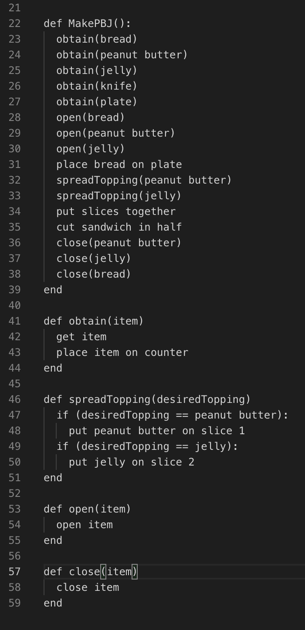

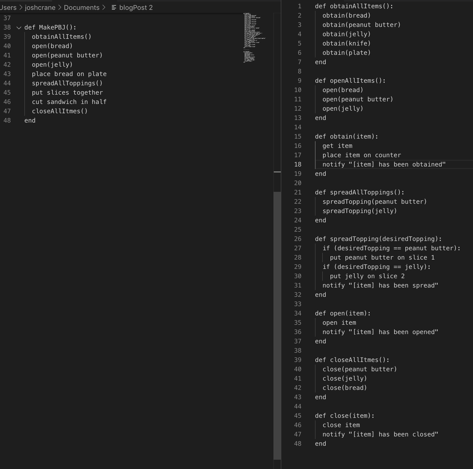

Figure 2: Functions were created to carry out the same task with various parts of the sandwich

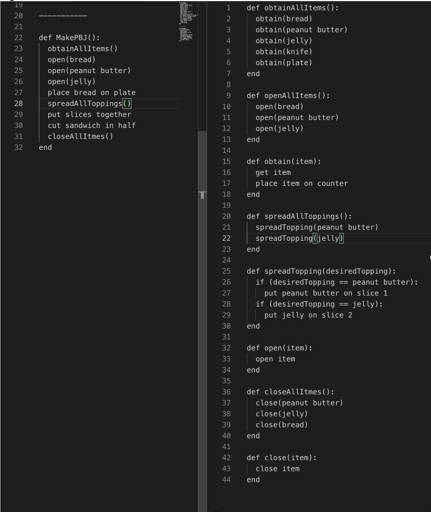

Figure 3: Placing smaller functions elsewhere makes the main program more legible

In this step, the single unique functions were generalized into something that can be reused. But the number of lines in the main function has not been reduced. In Figure 2 and 3, those functions were leveraged to reduce those lines in the main code.

We have reduced the lines of code in the main program and added other functions that carry out single tasks. On the surface, it looks like more complexity was added, but why? The changes made above allow more flexibility. A simple example is to consider that we may want to know when each action occurs successfully, as if reading a log file. In Figure 1, the user is required to painstakingly add logging after each line as seen in Figure 4.

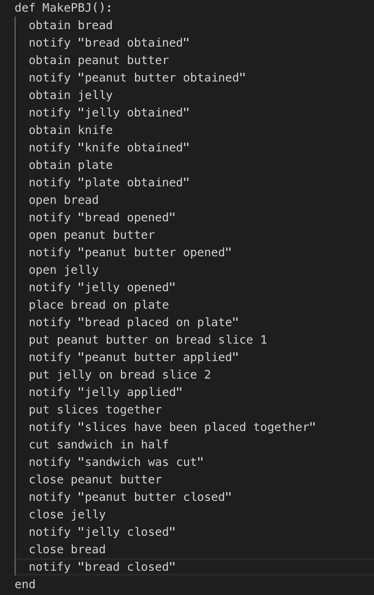

Figure 4: Each log message is added individually

Figure 5: Fewer lines of code are modified to achieve the same logging

In the other corner, Figure 5 shows how we can add the same amount of logging but with fewer lines. By placing those notify messages in the lowest level functions, they are invoked each time an action occurs without doubling the size of the main program.

In the case of the peanut butter & jelly sandwich, the consequences for working without different layers of code are relatively small. During programming of a robotic cell, these consequences are magnified, and harder to resolve. The above example shows only the tip of the iceberg regarding the concept of abstraction.

Debugging

Imagine a road that has been maintained by placing patches on each hole and bump. Imagine this road being further patched when the initial patches began to deteriorate. In fact, those who live in a climate with large temperature swings may not need to imagine at all - this describes their daily commute.

This analogy may pertain to code that is written without abstraction. At first a seemingly pristine program is written. After the needs of the robot change or a bug is found, a piece of code might be rewritten or replaced. Perhaps a new function or thread is introduced. If this cycle persists, programmers wake up one morning to find what was a concise and legible robot program is now a collection of various troubleshooting ideas. Debugging is much harder and tracing errors to their source is be a struggle of its own.

Layers of abstraction allows users to change one part of code or add functionality without harming the main program. It is best to make changes away from the main program, that will address the instances that need perfecting and will not modify the working code. A good rule of thumb is that one of piece of code should do one thing. Then all these pieces should be tied together in a main program or logic flow. This can be done in URScript, or in PolyScope itself through the use of folders and scripts.

Building in abstraction during robot programming allows more flexibility in the present and in the future. It makes coding easier and less time consuming. Lastly, it clarifies problems in the future and better facilitate general code changes as needs change. The benefits increase with time, since the code can be maintained, even by those who did not directly contribute to it at the start of production. With a bit of practice, time and headaches will dwindle away using the art of abstraction.