Recycle, Recycle, Recycle

by Josh Crane, on Oct 1, 2019 3:47:00 PM

Whether checking out at the grocery store or transporting civilians to Mars, reusable tools and resources are in high demand. Indeed, being able to use an existing asset means achieving goals faster, and at less cost.

After spending most of my time in a mechanically based world, I routinely leveraged existing tools to reach my goals. If design was required it occurred with several uses in mind. Even so, when I was asked to contribute to some application-specific programs for our robots, I forgot some of these ideas; I was locked into thinking of each robot as an island, when really there are several common themes that permeate our team of robotic employees.

Over time, I have come to treat various pieces of code as building blocks or puzzle pieces, that we can place together to generate a program without substantial debugging time. Most of the logic and I/O are similar between robots; only the robot motion and waypoints are unique to each application. The end goal a large tool box full of files or pieces of code that can be combined, reducing the need for unique and complex code to zero.

Here, I will focus on Polyscope. Polyscope is the language used by Universal Robots to simplify and accelerate robotic programming for those new to the world of programming. What follows is a simple overview of helpful tools and where they may be the most useful in creating reusable code.

Folders

Folders are used the same way they are used on a computer: to organize. Any line that can be added to a PolyScope program can be cut and pasted into a folder. From there, the folder can be named and collapsed, and moved to anywhere in the program. Once a folder is created, lines can be added or removed without affecting other folders. Folders are the quickest way to make code reusable, and can be used for a point of reference. Like a comment, folders with a bold title indicate where a certain piece of code is found.

Subprograms

If one file is truly desired, a subprogram may be the answer. A subprogram lives in one place, at the bottom of the program, and users can see program execution as they are run. Once a subprogram is created, it can be called from anywhere in the program. In addition, they are built using the same syntax as the main robot program, unlike script files. The big catch? A subprogram cannot be called from within another subprogram. The building block analogy fails

here as subprograms cannot be built from one another, which may be a drawback. Subprograms are a good solution when you can create one method to accomplish a task that will be done multiple times throughout a program.

Script Files

If subprograms are a standard family sedan, scripts are a fully adjustable racecar. They provide the greatest amount of control and flexibility, but require a steeper learning curve. A good reference is UR’s script manual, which is very helpful in providing syntax and examples of commonly used functions. Scripts are written in a slightly different syntax and in a different environment. This means scripts can also be written in common IDE’s from Microsoft Visual Studio to Windows Notepad. In fact, these scripts can be tested outside the robot program, reducing headaches during troubleshooting. Script files can be called from within one another, making them ideal as building blocks to create a concise and reusable robot program. They can be saved to the controller and used across multiple programs on the robot, ideal characteristics of building blocks in programming. Scripts are excellent in carrying out a function repeatedly throughout the program, or to do a very basic task with some added logic.

Tools in Practice

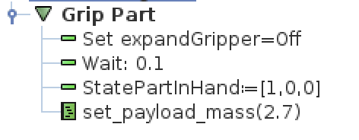

A good example of these three tools at work is the use of a gripper. When using the folder, the desired actions are placed in order and follow typical PolyScope syntax. All lines must be created separately. That makes writing code which carries out numerous actions time consuming as the folder must be copied to each place where it is needed.

Folders will be bolded and everything inside will be indented

A subprogram, like a folder, is written once. Rather than being copied, it is called within the program where needed, and takes up space after the robot program and before threads, which can ease the pain when navigating large programs.

The subprogram is denoted by a ‘P’, and it’s actions are indented under the bolded title

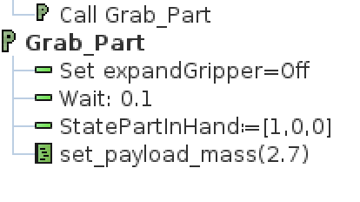

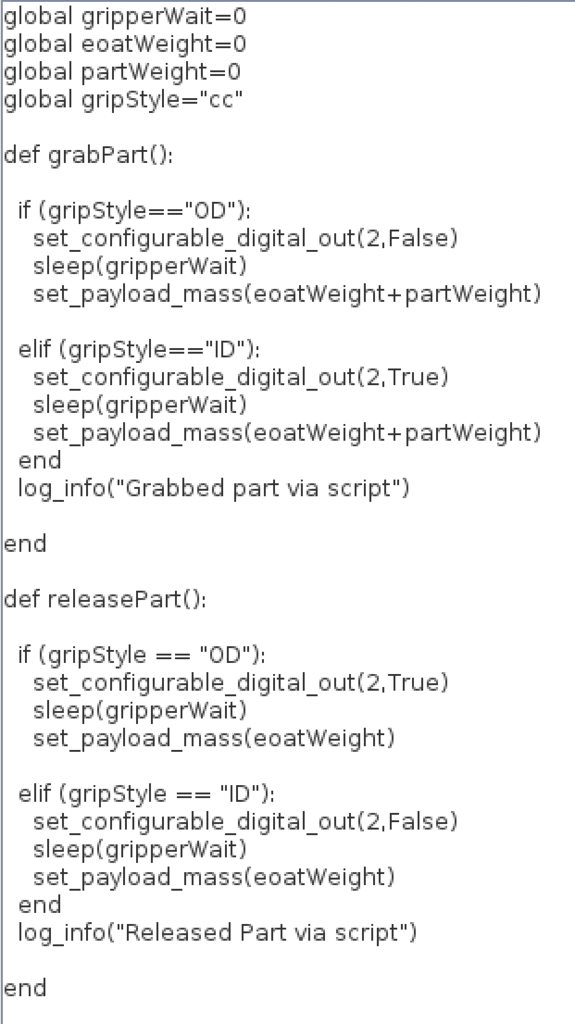

Using a script will require the most forethought, but can be made to address many situations based on what is passed into the function. The particular example shown is a script controlling a gripper that also controls variables pertaining to the part and gripper. For instance, this script can be told whether the grip is an outer diameter or inner diameter grip, and can grab or release the part without a human having to decide whether an input should be set on or off for the grip/release process. The script is saved in the controller and is called with just one line in the final program. This makes the program easier to navigate and expedites troubleshooting as users are not wading through numerous lines of code.

The script file is called in one line, at any time after the script file is written

Users must utilize proper syntax and formatting, but will gain the ability to do much more with each line of code

No matter the task at hand, reuse of hardware and software is a fast pass for efficiency. Folders, subprograms, and scripts are great methods for making code easier to create, debug, and reuse. Whether you are looking to utilize a robotic fleet more effectively or integrate a single cell, try these out and see what works!